Plant evolutionary genomics

in contemporary environments

Contemporary environmental change not only reshapes our landscapes—driving species to invade and go extinct—but also provides a natural laboratory for studying how selection reshapes genomic variation across populations in real time.

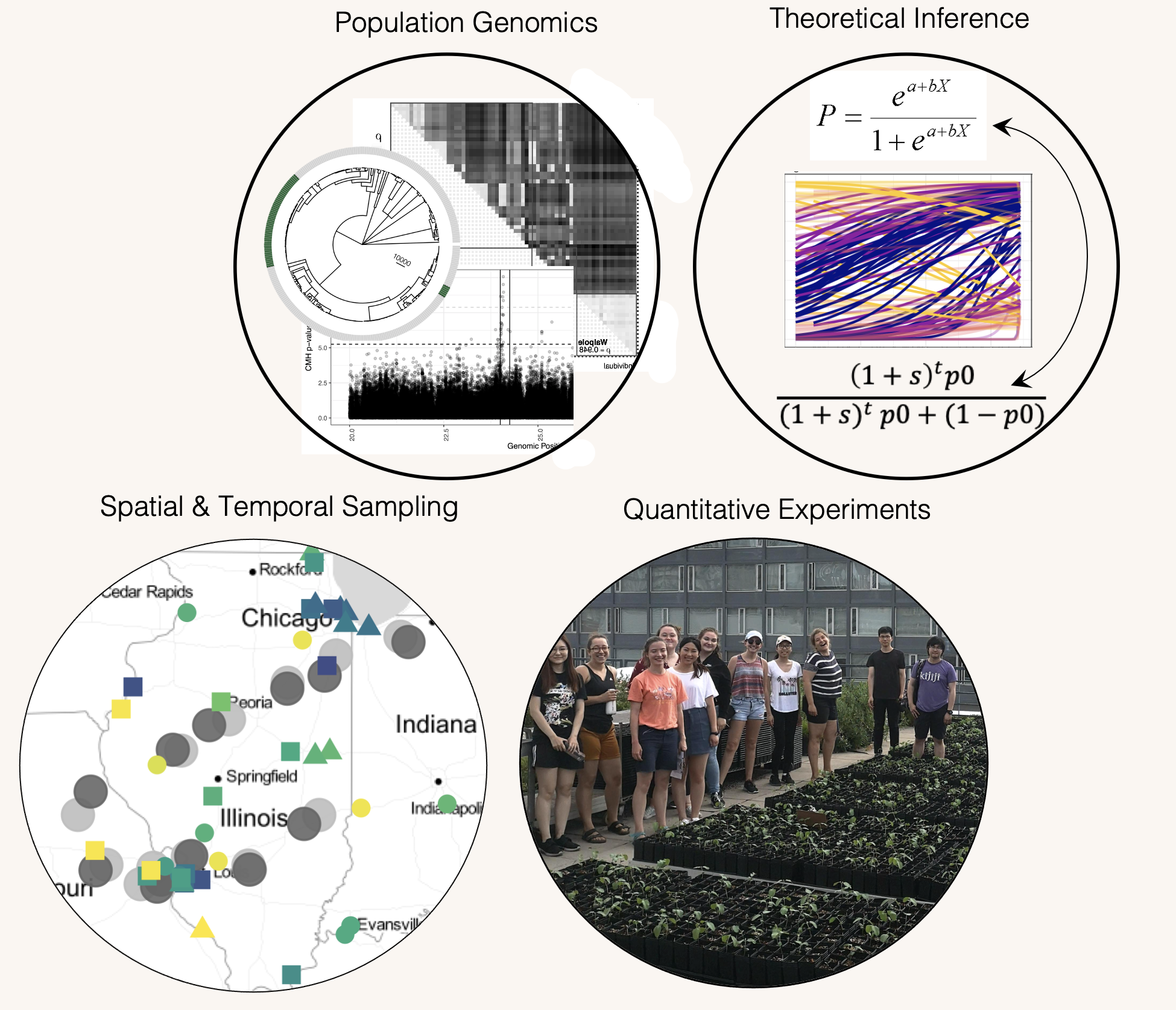

Our lab uses population genomics to dissect the nature and architecture of adaptive variation across contemporary landscapes. We combine spatiotemporal sampling (contemporary, historical, and ancient) with large-scale sequencing and experiments to reconstruct evolution in systems of pressing

importance—from agricultural pests to species at risk.

Our work addresses several fundamental questions in evolutionary genetics:

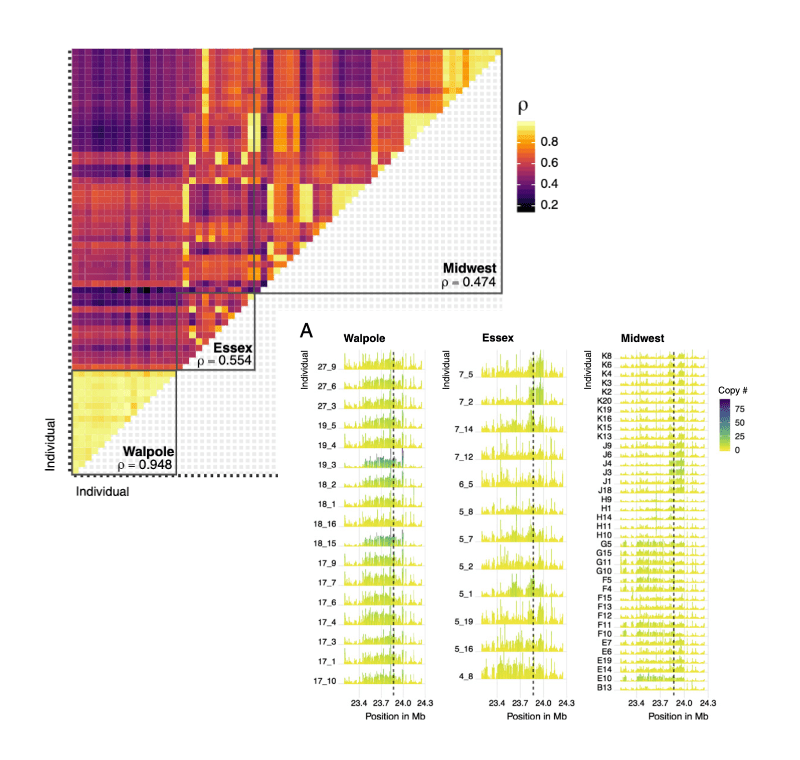

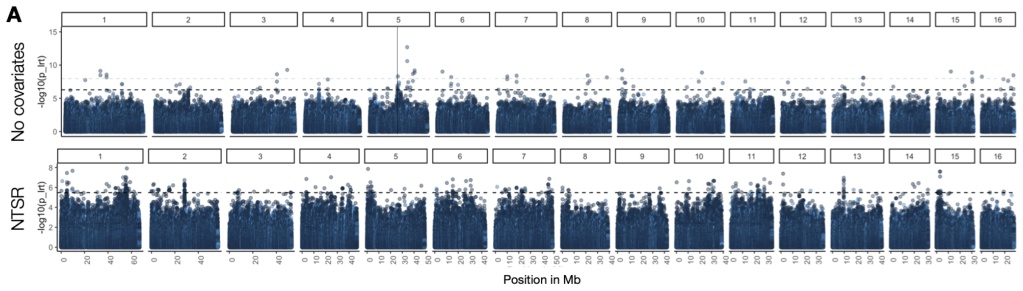

- What is the genetic architecture of adaptive variation?

- To what extent does adaptation occur through novel mutation, standing genetic variation, or gene flow?

- What is the distribution of phenotypic effect sizes across genome?

- How heterogenous are trait genetic architectures across populations experiencing parallel selection?

- What limits the tempo of adaptation?

- How does fluctuating selection through space and time influence evolution over broader scales?

- To what extent does migration reshape the rate and nature of variants responding to selection?

- How do differences among population and species (e.g. mating system, ploidy, dispersal mode)

influence the nature of responses to environmental change?

To address these questions, the lab uses cutting-edge population genomic approaches—from ancestral recombination graphs and GWAS to various methods of selective inference—bolstered by spatial and temporal sampling designs, theoretical inference, and quantitative genetic experiments in non-model organisms. A distinguishing feature of our work is leveraging herbarium (plant museum) specimens that span centuries to directly observe adaptive allele frequency change.

We have developed waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) as a model system with these approaches; As a native species that predates agricultural conversion of the Midwest, specimens from the 1800s to present along with contemporary samples across natural and agricultural environments have revealed the genomic transitions underlying its rise as one of the most problematic weeds in the US. More broadly, the repeated evolution of herbicide resistance and weediness under industrial agriculture provides replicate case studies for understanding the predictability of adaptation—principles our lab is extending across several additional species responding to contemporary environmental change.

Read more about these interests below